Campaign is committed to helping victims of sexual harassment get their experiences heard without compromising their safety. To get in contact with us to share a story, please see the box at the bottom of this page.

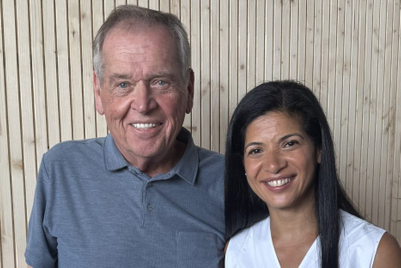

The seemingly slow progress of the #MeToo movement in India’s advertising industry is typical of what’s happening in the fight to expose sexual harassment everywhere else in the world, Cindy Gallop tells Campaign Asia-Pacific. The advertising executive hopes women take heart, however, from her conviction that it is "absolutely progressing", and will do so the more women come forward and speak out.

Shocking stories of a range of abuse, from bullying to rape, first emerged from several Indian industries in October 2018. Momentum built following widespread press coverage and soon spread into the advertising world, where many women spoke out and a few men were fired.

But seven months on, talk and action has quieted down significantly in adland, which prompted Gallop to tell an Indian newspaper a few weeks ago that the whole movement has been “far from a success”.

“What you get is a few very brave women speaking up, you get immediate coverage, and you get immediate public statements from the agencies involved," the English advertising professional, who founded the US branch of BBH and the video-sharing site Make Love Not Porn, tells Campaign during a recent trip to Asia. "A few men lose their jobs, but investigations are not carried out in the appropriate way.

“My observation is certainly that there is a very clear air, from the agencies involved, of ‘Oh my God, got to be seen to be doing something, we'll launch an investigation’, and lots of empty statements about ‘We have zero tolerance’ or blah blah. A real desire to be seen to be doing the appropriate thing but not really doing the appropriate thing.”

In India, among those who were fired following allegations of sexual harassment last year were Publicis’s Ishrath Nawaz, four executives from DAN and YRF’s Ashish Patil. But Gallop, who first called on victims of sexual harassment in adland to speak out in October 2017, is certain that many more who deserved the same justice will have escaped losing their jobs. This is the reason most agencies haven’t moved beyond “damage limitation” to endemic change.

“When the men at the top everywhere are themselves responsible for driving that culture from the top, and some of their mates were unlucky enough to get exposed and found out, you can bet there's a tonne of ‘Thank God it wasn’t me’ going on,” says Gallop. “Therefore they are not motivated or dedicated to eradicating this once and for all within their agencies.”

India's #MeToo: both unique and universal

While she’s seen “pretty much the same” state of affairs in every region around the world, Gallop, who is based in New York, acknowledges that in India’s case she speaks as an outsider. She followed what was happening last October via Ketaki Rituraj, an advertising professional with over 10 years’ experience, who tracked and shared all #MeToo developments in the ad world on Twitter.

Rituraj herself agrees that India’s #MeToo movement can’t (yet) be labelled a success, although talk and a heightened awareness about it continues to this day. “It all began with a bang, and I'm glad to see that many harassers were put in the dock of public opinion... but that's ... pretty much it,” she writes to Campaign in an email interview. “At least as far as the advertising industry is concerned, it fizzled out soon after, primarily because it was incredibly difficult for most of the women survivors to actually prove their cases. Legally this is a very tough battle, tougher in India where many of the survivors had never even told family and friends about what they went through, and continue to want to remain anonymous.”

The legal and privacy complexities that can occur around sexual harassment cases are something Gallop feels strongly about. One of her main aims has been to persuade victims of sexual harassment that it’s OK to break NDAs (non-disclosure agreements) they may have signed preventing them from speaking out. “I use the example of a couple of Harvey Weinstein's victims who did that,” she says. “A), it’s OK to break an NDA and b), you may have signed an NDA but your partner didn't. Your family didn’t. Your friends didn’t. The people who know what went on because you confided in them can absolutely speak up on your behalf.”

|

How clients have responded Perhaps the most high-profile client action took place around Suhel Seth, the founder of the agency Counselage. Seth was accused of sexual harassment by a number of women, including the Indian model and TV show host Diandra Soares and the writer Ira Trivedi, in October 2018. In response, Tata Group terminated its contract with Counselage. Coca-Cola, which had had a long-term relationship with Seth and his agency, said he was "not a consultant for the board or company presently"; other firms he had worked with, such as Adani Group and Mahindra Group, publically confirmed they were not working with him. Seth, a prolific Tweeter with 4.81 million Twitter followers, has not shared anything on the social-media site since October 11, and has not spoken publically about the allegations. A talk he was due to give in January at The Ivy League CEO forum in Indore was cancelled, and Counselage's website does not appear to be fully functioning. There are few other clear instances of brands breaking connections over MeToo allegations, however, or even confirming their working status with the agencies involved. According to Rituraj, the mega-conglomerate Reliance Industries, a client of the agency Utopeia Communicationz, whose founder Sudarshan Banerjee was accused of sexual harassment, considered withdrawing from or not awarding large campaigns to the agency. It is still listed on Utopeia's website as a client today, and the company has not yet responded to Campaign’s request for comment. (Reliance had its own #MeToo problems: the head of its in-house content studio, Ajit Thakur, resigned after being accused of sexual harassment by Supriya Prasad, a writer from the Film and Television Institute of India.) The conglomerate Godrej, meanwhile, was reportedly approached by employees from the agency Creativeland Asia (CLA) — where many allegations emerged against founder and creative chairman Sajan Raj Kurup — hoping the brand’s weight would help pressure the agency into action when their original public statement responding to the claims didn't mention any investigation.

Sajan Raj Kurup's profile on CreativeLand's homepage (far left), where an updated 'Anti sexual harassment policy' is also clearly on display.

Godrej’s chairperson Nisaba Godrej stated at the time the allegations emerged: “We will not do business with any organisation where it is proven that discrimination or harassment is prevalent and tolerated”. Kurup remains in his seat and CLA remains the company’s agency, according to CLA's website, suggesting Godrej found a way to feel confident that the claims against Kurup were false. When Campaign approached Godrej to ask how they ascertained that harassment or discrimination was not present at CLA, the company said they "would like to avoid commenting for this article". CLA has not yet responded to Campaign's requests for more information. |

Gallop is also emphatic that in the current climate, no agency or holding company would pursue a #MeToo victim for breaking an NDA because “they can’t afford to”, from either a financial or a reputational standpoint.

But even if she can convince women to share their experiences, Rituraj’s point about the additional hurdles that come with speaking out in India comes into play. Gallop accepts that without substantial access to legal funds, bringing harassers to justice remains a goal that’s still out of reach for many individuals.

In a case covered by Campaign last year, for example, several claims were published against Sudarshan Banerjee, founder of the Indian agency Utopeia, whose lawyers issued a letter declaring three of them “figments of imagination” (a fourth was labelled a “twisted and distorted and embellished version of an old and closed Human Resources (HR) issue”) and saying Banerjee would only deal further with the allegations if the “supposed victims” challenged him in the courts.

Such circumstances are “absolutely appalling” says Gallop, who remembers the case. “Obviously nobody has the money for lawyers and legal fees in this scenario.” It exemplifies something she has observed all the way through the movement—that the immediate response of men accused of harassment is to “deny, deny, deny.”

The winds of change

This may be gradually shifting. “The old-world-order male response is to believe that if you come out swinging with enough bluster and bravado and deny everything—and, by the way, they are obviously being advised accordingly by their male lawyers to do this—there is a misguided and mistaken belief that you can make all this go away," Gallop says. "And you can absolutely temporarily stall women who do not have money for lawyers’ fees in the same way that you do.” But many men are now beginning to realise that this response is no longer a solution because it screams “guilty”, she adds.

Reports suggest there have been serious consequences for people and agencies hit with claims (see box, above), whether or not an investigation took place or the alleged harasser was found guilty or innocent. The lawyer for Banerjee says his business has suffered major financial and staff losses. Of the 42 employees named on Utopeia's website, only 11 have not had their profiles replaced with a generic "We're currently looking for junior copywriters" message, suggesting a mass exodus.

(Three weeks ago, after Banerjee lodged a request for a police First Information Report, police in Mumbai arrested an advertising post-graduate called Utkarsh Mehta, whom they had traced as the creator of the email addresses and online profiles used to share the claims against Banerjee. When questioned, Mehta reportedly said he had set up the email addresses and made posts on behalf of his female friends who had experienced harassment. He is being held on various charges including forgery for purpose of harming reputation.)

But despite Utopeia's reported loss of business, Rituraj says she is disappointed more clients haven't taken a stand, especially as brands are usually so quick to distance themselves from any hint of controversy. "The client-agency 'relationship' prevailed eventually”, in many cases, she thinks: until more clients support the #MeToo movement and boycott people and companies where sexual harassment has been called out, agencies will be “content to carry on as if nothing happened”.

Young people may in fact end up being more powerful drivers of change, Rituraj says. “One impact that I've noticed is the shying away of young talent from any agency that's been accused. Naturally—they hardly want to begin their careers with a 'tainted' agency and questionable work culture!”

Gallop stresses that while there are reasons to despair that little is changing, each wave of the #MeToo movement around the world sees women feeling more and more angry and motivated to speak out.

“This is why I enjoin women to get really angry," she says. "Anger makes things happen. And we are mad as hell, and we are not going to take it anymore.”

|

Reporting sexual harassment and finding support Campaign is committed to helping victims of sexual harassment to get their stories heard without compromising their safety. If you would like to report an incident you have experienced or seen, we welcome your contact via any of the below means and will grant anonymity if it is requested. Some sources of support in Asia

Australia

China

Hong Kong

Singapore:

South Asia and India:

|

.jpg&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.jpg&h=268&w=401&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=268&w=401&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=268&w=401&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)