Revlon, a US cosmetics brand that entered China in 1996, is pulling out due to steadily falling sales. The exit will result in the loss of 1,100 jobs and annual savings of US$11 million.

With China’s cosmetics market worth more than $25 billion a year, and expected to grow 8 per cent each year over the next three years, according to Euromonitor, Revlon’s failure indicates deep-seated problems. Since its entry into the market, Revlon has adopted only a single distribution channel to market its brands, Revlon and Almay, in 50 of China’s 160 cities. The brand has also never launched products specifically aimed at Asian tastes.

Revlon’s US-centric approach may even be harming its prospects in the rest of the region. Last year, the makeup company made $166 million sales in Asia-Pacific, a drop of 3.5 per cent.

What lessons does the brand need to learn from China to halt the slide and save its business in Asia?

Fact file:

- China only accounted for 2 per cent of its total sales in 2012

- In China, Revlon holds only 1 per cent share of the makeup market, and 0.1 per cent of the skincare market according to Kantar Worldpanel China

|

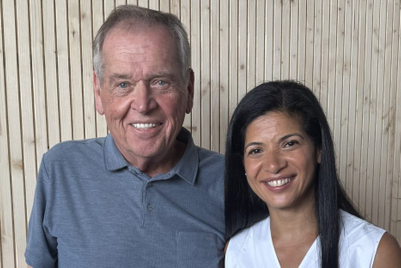

DIAGNOSIS 1 Richard Summers

With the likes of L’Oréal signalling serious commitment to the market by opening an R&D centre in China, tailoring your offering to local audiences is a must. Revlon’s failure to innovate locally will have limited their appeal. As local and Korean brands have become increasingly influential, Revlon has fallen between two stalls: neither aspirational for the top-end end of the market, nor affordable for the lower end. Meanwhile, although savvy consumers have shifted their attention and spending online, Revlon’s has stuck to counters. With a plethora of cosmetic shopping portals to choose from — Jumei, Lefeng, JD and, of course, Tmall — this method is somewhat archaic. In contrast, brands such as Lancôme have embraced this shift creating platforms like Rose Beauty. In the end, it may come down to the simple fact that consumers just want to try something new. This is a highly competitive category driven by innovation, and Revlon has become a brand of a bygone era. Their exit shows the days of simply showing up and selling are over. Richard Summers is head of strategic planning at Anomaly Shanghai |

DIAGNOSIS 2 Tom Evrard

While luxury products and beauty are at the epicentre of consumption behaviour, capitalising on those trends remains challenging even for brands with strong global reputations. The unhindered growth of global retail and cosmetics groups in China has slowed considerably in the wake of shifting consumer trends, a war for customer loyalty, and a softening macroeconomic climate. Revlon lacked the ability to establish substantial market share with its namesake brand, natural Almay cosmetics and cheap and cheerful Sinful Colours. Indeed local sales accounted for just two per cent of Revlon’s global total, indicating its lack of operational adaptability in the market. Its retail strategy, which included distribution in both boutiques and supermarkets, it seems to suffer from a brand identity crisis. Contrast this with the success of the Estée Lauder brands, which have focused relentlessly on the top end of the market. Estée Lauder has also adopted a deep localisation strategy, including developing a new brand exclusively for China. Revlon has never able to achieve this level of innovation or relevance to local consumers. Tom Evrard is MD of FTI Consulting |

Despite being one of the first international brands to enter the market, rather than capitalise on their good awareness and create products for local complexions, they stuck with their global (or for many, decidedly ‘American’) offering.

Despite being one of the first international brands to enter the market, rather than capitalise on their good awareness and create products for local complexions, they stuck with their global (or for many, decidedly ‘American’) offering. Revlon’s withdrawal from China is among a series of economic indicators illustrating that the explosion in the country’s cosmetics market is producing both winners and losers.

Revlon’s withdrawal from China is among a series of economic indicators illustrating that the explosion in the country’s cosmetics market is producing both winners and losers..jpg&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)

.png&h=334&w=500&q=100&v=20250320&c=1)